Methotrexate

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation |

|

| Trade names | Trexall, Rheumatrex, others[4] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682019 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, IV, IM, SC, intrathecal |

| ATC code | L01BA01 (WHO) L04AX03 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60% at lower doses, less at higher doses.[5] |

| Protein binding | 35–50% (parent drug),[5] 91–93% (7-hydroxymethotrexate)[6] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic and intracellular[5] |

| Biological half-life | 3–10 hours (lower doses), 8–15 hours (higher doses)[5] |

| Excretion | Urine (80–100%), faeces (small amounts)[5][6] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

59-05-2 |

| PubChem (CID) | 126941 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 4815 |

| DrugBank |

DB00563 |

| ChemSpider |

112728 |

| UNII |

YL5FZ2Y5U1 |

| KEGG |

D00142 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:44185 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL34259 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.376 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

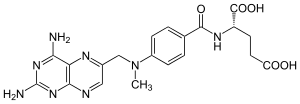

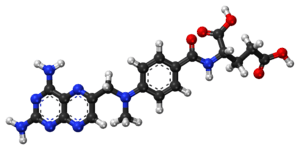

| Formula | C20H22N8O5 |

| Molar mass | 454.44 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Methotrexate (MTX), formerly known as amethopterin, is a chemotherapy agent and immune system suppressant.[4] It is used to treat cancer, autoimmune diseases, ectopic pregnancy, and for medical abortions. Types of cancers it is used for include breast cancer, leukemia, lung cancer, lymphoma, and osteosarcoma. Types of autoimmune diseases it is used for include psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Crohn's disease. It can be given by mouth or by injection.[4]

Common side effects include nausea, feeling tired, fever, increased risk of infection, low white blood cell counts, and breakdown of the skin inside the mouth. Other side effects may include liver disease, lung disease, lymphoma, and severe skin rashes. People on long-term treatment should be regularly checked for side effects. It is not safe during breastfeeding. In those with kidney problems, lower doses may be needed. It acts by blocking the body's use of folic acid.[4]

Methotrexate was first made in 1947 and came into medical use initially to treat cancer, as it was less toxic than other available agents.[7] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[8] Methotrexate is available as a generic medication.[4] The wholesale cost as of 2014 in the developing world is between US$0.06 and 0.36 per day for the form taken by mouth.[9] In the United States, a typical month of treatment costs $25 to $50.[10]

Medical uses

Chemotherapy

Methotrexate was originally developed and continues to be used for chemotherapy, either alone or in combination with other agents. It is effective for the treatment of a number of cancers, including: breast, head and neck, leukemia, lymphoma, lung, osteosarcoma, bladder, and trophoblastic neoplasms.[4]

Autoimmune disorders

It is used as a disease-modifying treatment for some autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile dermatomyositis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, lupus, sarcoidosis, Crohn's disease (although a recent review has raised the point that it is fairly underused in Crohn's disease),[11] eczema and many forms of vasculitis.[12][13] Although originally designed as a chemotherapy drug (using high doses), in low doses, methotrexate is a generally safe and well tolerated drug in the treatment of certain autoimmune diseases. Because of its effectiveness, low-dose methotrexate is now first-line therapy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Weekly doses are beneficial for 12 to 52 weeks duration therapy, although discontinuation rates are as high as 16% due to adverse effects.[14] Although methotrexate for autoimmune diseases is taken in lower doses than it is for cancer, side effects such as hair loss, nausea, headaches, and skin pigmentation are still common.[12][15][16] Use of methotrexate together with NSAIDS is safe, if adequate monitoring is done.[17]

It use in lupus is uncommon with only tentative evidence to support it.[18]

Not everyone is responsive to treatment with methotrexate, but multiple studies and reviews showed that the majority of people receiving methotrexate for up to one year had less pain, functioned better, had fewer swollen and tender joints, and had less disease activity overall as reported by themselves and their doctors. X-rays also showed that the progress of the disease slowed or stopped in many people receiving methotrexate, with the progression being completely halted in about 30% of those receiving the drug.[19] Those individuals with rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate have been found to have a lower risk of cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarctions (heart attacks) and strokes.[20] It has also been used for multiple sclerosis.[4]

Abortion

Methotrexate is an abortifacient and is commonly used to terminate pregnancies during the early stages, generally in combination with misoprostol. It is also used to treat ectopic pregnancies, provided the fallopian tube has not ruptured.[4][21]

Molar pregnancy

Methotrexate with dilatation and curettage is used to treat molar pregnancy.

Administration

Methotrexate can be given by mouth or by injection (intramuscular, intravenous, subcutaneous, or intrathecal).[4] Doses by mouth are usually taken weekly, not daily, to limit toxicity.[4] Routine monitoring of the complete blood count, liver function tests, and creatinine are recommended.[4] Measurements of creatinine are recommended at least every 2 months.[4]

Adverse effects

The most common adverse effects include: hepatotoxicity (liver damage), ulcerative stomatitis, leukopenia and thus predisposition to infection, nausea, abdominal pain, fatigue, fever, dizziness, acute pneumonitis, rarely pulmonary fibrosis, and kidney failure.[12][4] Methotrexate is teratogenic (harmful to a fetus), hence is not used in pregnancy (pregnancy category X).

Central nervous system reactions to methotrexate have been reported, especially when given via the intrathecal route (directly into the cerebrospinal fluid), which include myelopathies and leucoencephalopathies. It has a variety of cutaneous side effects, particularly when administered in high doses.[22]

Another little understood but serious possible adverse effect of methotrexate is neurological damage and memory loss. Neurotoxicity may result from the drug crossing the blood–brain barrier and damaging neurons in the cerebral cortex. Cancer patients who receive the drug often nickname these effects "chemo brain" or "chemo fog".[23]

Drug interactions

Penicillins may decrease the elimination of methotrexate, so increase the risk of toxicity.[4] While they may be used together, increased monitoring is recommended.[4] The aminoglycosides, neomycin and paromomycin, have been found to reduce gastrointestinal (GI) absorption of methotrexate.[24] Probenecid inhibits methotrexate excretion, which increases the risk of methotrexate toxicity.[24] Likewise, retinoids and trimethoprim have been known to interact with methotrexate to produce additive hepatotoxicity and haematotoxicity, respectively.[24] Other immunosuppressants like ciclosporin may potentiate methotrexate's haematologic effects, hence potentially leading to toxicity.[24] NSAIDs have also been found to fatally interact with methotrexate in numerous case reports.[24] Nitrous oxide potentiating the haematological toxicity of methotrexate has also been documented.[24] Proton-pump inhibitors such as omeprazole and the anticonvulsant valproate have been found to increase the plasma concentrations of methotrexate, as have nephrotoxic agents such as cisplatin, the GI drug colestyramine, and dantrolene.[24] Caffeine may antagonise the effects of methotrexate on rheumatoid arthritis by antagonising the receptors for adenosine.[5]

Mechanism of action

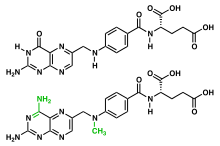

Methotrexate is an antimetabolite of the antifolate type. It is thought to affect cancer and rheumatoid arthritis by two different pathways. For cancer, methotrexate competitively inhibits dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), an enzyme that participates in the tetrahydrofolate synthesis.[25][26] The affinity of methotrexate for DHFR is about 1000-fold that of folate. DHFR catalyses the conversion of dihydrofolate to the active tetrahydrofolate.[25] Folic acid is needed for the de novo synthesis of the nucleoside thymidine, required for DNA synthesis.[25] Also, folate is essential for purine and pyrimidine base biosynthesis, so synthesis will be inhibited. Methotrexate, therefore, inhibits the synthesis of DNA, RNA, thymidylates, and proteins.[25]

For the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, inhibition of DHFR is not thought to be the main mechanism, but rather multiple mechanisms appear to be involved, including the inhibition of enzymes involved in purine metabolism, leading to accumulation of adenosine; inhibition of T cell activation and suppression of intercellular adhesion molecule expression by T cells; selective down-regulation of B cells; increasing CD95 sensitivity of activated T cells; and inhibition of methyltransferase activity, leading to deactivation of enzyme activity relevant to immune system function.[27][28] Another mechanism of MTX is the inhibition of the binding of interleukin 1-beta to its cell surface receptor.[29]

History

In 1947, a team of researchers led by Sidney Farber showed aminopterin, a chemical analogue of folic acid developed by Yellapragada Subbarao of Lederle, could induce remission in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The development of folic acid analogues had been prompted by the discovery that the administration of folic acid worsened leukemia, and that a diet deficient in folic acid could, conversely, produce improvement; the mechanism of action behind these effects was still unknown at the time.[30] Other analogues of folic acid were in development, and by 1950, methotrexate (then known as amethopterin) was being proposed as a treatment for leukemia.[31] Animal studies published in 1956 showed the therapeutic index of methotrexate was better than that of aminopterin, and clinical use of aminopterin was thus abandoned in favor of methotrexate.

In 1951, Jane C. Wright demonstrated the use of methotrexate in solid tumors, showing remission in breast cancer.[32] Wright's group was the first to demonstrate use of the drug in solid tumors, as opposed to leukemias, which are a cancer of the marrow. Min Chiu Li and his collaborators then demonstrated complete remission in women with choriocarcinoma and chorioadenoma in 1956,[33] and in 1960 Wright et al. produced remissions in mycosis fungoides.[34][35]

References

- ↑ "methotrexate - definition of methotrexate in English from the Oxford dictionary". OxfordDictionaries.com. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ↑ "methotrexate". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ↑ "methotrexate". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Methotrexate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 22 Aug 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Trexall, Rheumatrex (methotrexate) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- 1 2 Bannwarth, B; Labat, L; Moride, Y; Schaeverbeke, T (January 1994). "Methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. An update.". Drugs. 47 (1): 25–50. doi:10.2165/00003495-199447010-00003. PMID 7510620.

- ↑ Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 251. ISBN 9780470015520.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Methotrexate Sodium". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 464. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ Herfarth HH, Long MD, Isaacs KL (2012). "Methotrexate: underused and ignored?". Digestive Diseases. 30 Suppl 3: 112–8. doi:10.1159/000342735. PMID 23295701.

- 1 2 3 Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ↑ Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ↑ Lopez-Olivo, MA (2014). "Methotrexate for treating rheumatoid arthritis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): Art. No.: CD000957. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000957.pub2. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ↑ Cronstein, B. N. (2005). "Low-Dose Methotrexate: A Mainstay in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis". Pharmacological Reviews. 57 (2): 163–172. doi:10.1124/pr.57.2.3. PMID 15914465.

- ↑ American , Rheumatoid Arthritis Guidelines (2002). "Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002 update". Arthritis Rheum. 46: 328–346. doi:10.1002/art.10148.

- ↑ Colebatch, AN (2011). "Safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including aspirin and paracetamol (acetaminophen) in people receiving methotrexate for inflammatory arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, other spondyloarthritis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008872.pub2.

- ↑ Tsang-A-Sjoe, MW; Bultink, IE (2015). "Systemic lupus erythematosus: review of synthetic drugs.". Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 16 (18): 2793–806. PMID 26479437.

- ↑ Weinblatt, ME (2013). "Methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: a quarter century of development." (PDF). Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 124: 16–25. PMC 3715949

. PMID 23874006.

. PMID 23874006. - ↑ Marks JL, Edwards CJ (2 February 2012). "Protective effect of methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular comorbidity" (PDF). Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease. 4 (3): 149–157. doi:10.1177/1759720X11436239. PMC 3400102

. PMID 22850632.

. PMID 22850632. - ↑ Mol, F.; Mol, B.W.; Ankum, W.M.; Van Der Veen, F.; Hajenius, P.J. (2008). "Current evidence on surgery, systemic methotrexate and expectant management in the treatment of tubal ectopic pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 14 (4): 309–19. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmn012. PMID 18522946.

- ↑ Scheinfeld, N (2006). "Three cases of toxic skin eruptions associated with methotrexate and a compilation of methotrexate-induced skin eruptions". Dermatology online journal. 12 (7): 15. PMID 17459301.

- ↑ Hafner, D (2009). "Lost in the Fog: Understanding "Chemo Brain"". Nursing 2009. 39 (8): 42–45. doi:10.1097/01.nurse.0000358574.56241.2f.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Brayfield, A, ed. (6 January 2014). "Methotrexate". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Rajagopalan, P. T. Ravi; Zhang, Zhiquan; McCourt, Lynn; Dwyer, Mary; Benkovic, Stephen J.; Hammes, Gordon G. (2002). "Interaction of dihydrofolate reductase with methotrexate: Ensemble and single-molecule kinetics". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (21): 13481–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.172501499. PMC 129699

. PMID 12359872.

. PMID 12359872. - ↑ Goodsell DS (August 1999). "The Molecular Perspective: Methotrexate". The Oncologist. 4 (4): 340–341. PMID 10476546.

- ↑ Wessels, JA; Huizinga, TW; Guchelaar, HJ (March 2008). "Recent insights in the pharmacological actions of methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis." (PDF). Rheumatology. 47 (3): 249–55. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kem279. PMID 18045808.

- ↑ Böhm I. Increased peripheral blood B-cells expressing the CD5 molecules in association to autoantibodies in patients with lupus erythematosus and evidence to selectively down-modulate them. Biomed & Pharmacother 2004;58:338 - 343

- ↑ Brody M et al. Mechanism of action of methotrexate: experimental evidence that methotrexate blocks the binding of interleukin 1 beta to the interleukin 1 receptor on target cells. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1993;31(10):667-74

- ↑ Bertino JR (2000). "Methotrexate: historical aspects". In Cronstein BN, Bertino JR. Methotrexate. Basel: Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3-7643-5959-1. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ↑ Meyer, Leo M.; Miller, Franklin R.; Rowen, Manuel J.; Bock, George; Rutzky, Julius (1950). "Treatment of Acute Leukemia with Amethopterin (4-amino, 10-methyl pteroyl glutamic acid)". Acta Haematologica. 4 (3): 157–67. doi:10.1159/000203749. PMID 14777272.

- ↑ Wright, Jane C.; Prigot, A.; Wright, B.P.; Weintraub, S; Wright, LT (1951). "An evaluation of folic acid antagonists in adults with neoplastic diseases. A study of 93 patients with incurable neoplasms". J Natl Med Assoc. 43 (4): 211–240. PMC 2616951

. PMID 14850976.

. PMID 14850976. - ↑ Li, MC; Li, R; Spencer, DB (1956). "Effect of methotrexate upon choriocarcinoma". Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 93 (2): 361–366. doi:10.3181/00379727-93-22757. PMID 13379512.

- ↑ Wright, JC; Gumport, SL; Golomb, FM (1960). "Remissions produced with the use of methotrexate in patients with mycosis fungoides". Cancer Chemother Rep. 9: 11–20. PMID 13786791.

- ↑ Wright, JC; Lyons, M; Walker, DG; Golomb, FM; Gumport, SL; Medrek, TJ (1964). "Observations on the use of cancer chemotherapeutic agents in patients with mycosis fungoides". Cancer. 17 (8): 1045–1062. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(196408)17:8<1045::AID-CNCR2820170811>3.0.CO;2-S. PMID 14202592.

External links

- National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS) article on Methotrexate

- Chembank entry on methotrexate

- Methotrexate—general article from NIH

- Methotrexate Injection MedlinePlus article from NIH

- Patient Education - Methotrexate from American College of Rheumatology

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Methotrexate