Bangladesh

Coordinates: 23°48′N 90°18′E / 23.8°N 90.3°E

People's Republic of Bangladesh

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: "Amar Sonar Bangla" "My Golden Bengal" |

||||||

.svg.png) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Dhaka 23°42′N 90°21′E / 23.700°N 90.350°E | |||||

| Official languages | Bengali | |||||

| Recognized | English | |||||

| Ethnic groups (2011) | 98% Bengalis 2% Others[2] |

|||||

| Religion | 88% Islam 11% Hinduism 0.9% Others[2] |

|||||

| Demonym | Bangladeshi | |||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional republic | |||||

| • | President | Abdul Hamid | ||||

| • | Prime Minister | Sheikh Hasina | ||||

| • | Speaker of Parliament | Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury | ||||

| • | Chief Justice | Surendra Kumar Sinha | ||||

| Legislature | Jatiyo Sangshad | |||||

Independence from Pakistan | ||||||

| • | Declaration | 26 March 1971 | ||||

| • | Government | 17 April 1971 | ||||

| • | Liberation | 16 December 1971 | ||||

| • | Current constitution | 4 November 1972 | ||||

| • | Last territorial admission | 31 July 2015 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Total | 147,570[3] km2 (92nd) 56,977 sq mi |

||||

| • | Water (%) | 6.4 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 2015 estimate | 168,957,745[2] (8th) | ||||

| • | 2011 census | 149,772,364[4] (8th) | ||||

| • | Density | 1,319/km2 (10th) 3,416/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $572.440 billion[5] (34th) | ||||

| • | Per capita | $3,581[5] (144th) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $205.327 billion[5] (44th) | ||||

| • | Per capita | $1,284[5] (155th) | ||||

| Gini (2010) | 32.1[6] medium |

|||||

| HDI (2015) | medium · 142nd |

|||||

| Currency | Taka (৳) (BDT) | |||||

| Time zone | BST (UTC+6) | |||||

| Date format | ||||||

| Drives on the | left | |||||

| Calling code | +880 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | BD | |||||

| Internet TLD | .bd .বাংলা |

|||||

| Website bangladesh |

||||||

Bangladesh (![]() i/ˌbæŋɡləˈdɛʃ/; /ˌbɑːŋɡləˈdɛʃ/; বাংলাদেশ, pronounced: [ˈbaŋlad̪eʃ], lit. "The country of Bengal"), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh (গণপ্রজাতন্ত্রী বাংলাদেশ Gônôprôjatôntri Bangladesh), is a sovereign state in South Asia. It forms the largest and eastern portion the ethno-linguistic region of Bengal. Located at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, the country is bordered by India and Myanmar and is separated from Nepal and Bhutan by the narrow Siliguri Corridor.[8] With a population of 170 million, it is the world's eighth-most populous country, the fifth-most populous in Asia and the third-most populous Muslim-majority country. The official Bengali language is the seventh-most spoken language in the world, which Bangladesh shares with the neighboring Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam (Barak Valley).

i/ˌbæŋɡləˈdɛʃ/; /ˌbɑːŋɡləˈdɛʃ/; বাংলাদেশ, pronounced: [ˈbaŋlad̪eʃ], lit. "The country of Bengal"), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh (গণপ্রজাতন্ত্রী বাংলাদেশ Gônôprôjatôntri Bangladesh), is a sovereign state in South Asia. It forms the largest and eastern portion the ethno-linguistic region of Bengal. Located at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, the country is bordered by India and Myanmar and is separated from Nepal and Bhutan by the narrow Siliguri Corridor.[8] With a population of 170 million, it is the world's eighth-most populous country, the fifth-most populous in Asia and the third-most populous Muslim-majority country. The official Bengali language is the seventh-most spoken language in the world, which Bangladesh shares with the neighboring Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam (Barak Valley).

Three of Asia's largest rivers, the Ganges (locally known as the Padma), the Brahmaputra (locally known as the Jamuna) and the Meghna, flow through Bangladesh and form the fertile Bengal delta—the largest delta in the world.[9] With rich biodiversity, Bangladesh is home to 700 rivers; most of the Sundarbans, considered the world's largest mangrove forest; rainforested and tea-growing highlands; a 600 km (370 mi) coastline with one of the world's longest beaches; and various islands, including a coral reef. Bangladesh is one of the most densely populated countries in the world, ranking alongside South Korea and Monaco. The capital Dhaka and the port city of Chittagong are the most prominent urban centers. The predominant ethnic group are Bengalis, with a politically-dominant Bengali Muslim majority, followed by Bengali Hindus, Chakmas, Bengali Christians, Marmas, Tanchangyas, Bisnupriya Manipuris, Bengali Buddhists, Garos, Santhals, Biharis, Oraons, Tripuris, Mundas, Rakhines, Rohingyas, Ismailis and Bahais.[10]

Greater Bengal was known to the ancient Greeks and Romans as Gangaridai.[11] The people of the delta developed their own language, script, literature, music, art and architecture. Early Asian literature described the region as a seafaring power.[12] It was an important entrepot of the historic Silk Road.[13] Bengal was absorbed into the Muslim world and ruled by sultans for four centuries, including under the Delhi Sultanate and the Bengal Sultanate. This was followed by the administration of the Mughal Empire. Islamic Bengal was a melting pot, a regional power and a key player in medieval world trade. British colonial conquest took place in the late 18th century. Nationalism, social reforms and the arts developed under the British Raj in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the region was a hotbed of the anti-colonial movement in the subcontinent.

The first British partition of Bengal in 1905, that created the province of Eastern Bengal and Assam, set the precedent for the Partition of British India in 1947, when East Bengal joined the Dominion of Pakistan and was renamed as East Pakistan in 1955. It was separated from West Pakistan by 1,400 kilometres (870 mi) of Indian territory. East Pakistan was home to the country's demographic majority and its legislative capital.[14][15] The Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 resulted in the secession of East Pakistan as a new republic with a secular multiparty parliamentary democracy.[16][17][18] A short-lived one party state and several military coups in 1975 established a presidential government. The restoration of the parliamentary republic in 1991 led to improved economic growth and relative stability. Bangladesh continues to face challenges of poverty, corruption, polarized politics, human rights abuses by security forces, overpopulation and global warming. However, the country has achieved notable human development progress, including in health, education, gender equality, population control and food production.[19][20][21] The poverty rate has reduced from 57% in 1990 to 25.6% in 2014.[22]

Considered a middle power in international affairs and a major developing country, Bangladesh is listed as one of the Next Eleven. It is a unitary state with an elected parliament called the Jatiyo Sangshad. Bangladesh has the third-largest economy and military in South Asia after India and Pakistan. It is a founding member of SAARC and hosts the permanent secretariat of BIMSTEC.[23] The country is the world's largest contributor to United Nations peacekeeping operations.[24] It is a member of the Developing 8 Countries, the OIC, the Commonwealth of Nations, the World Trade Organization, the Group of 77, the Non-Aligned Movement, BCIM and the Indian Ocean Rim Association. The country has significant natural resources, including natural gas and limestone. Agriculture mainly produces rice, jute and tea. Historically renowned for muslin and silk, modern Bangladesh is one of the world's leading textile producers. Its major trading partners include the European Union, the United States, Japan and the other nearby nations of China, Singapore, Malaysia and India.

Etymology

The name Bangladesh was originally written as two words, Bangla Desh. Starting in the 1950s, Bengali nationalists used the term in political rallies in East Pakistan. The term Bangla is a major name for both the Bengal region and the Bengali language. The earliest references to the term date to the Nesari plate in 805 AD. The term "Vangaladesa" is found in South Indian records in the 11th century.[25][26][27]

The term gained official status during the Sultanate of Bengal in the 14th century.[28][29] Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah proclaimed himself as the first "Shah of Bangala" in 1342.[28] The word Bangla became the most common name for the region during the Islamic period. The Portuguese referred to the region as Bengala in the 16th century.[30]

The origins of the term Bangla are unclear, with theories pointing to a Bronze Age proto-Dravidian tribe,[31] the Austric word "Bonga" (Sun god),[32] and the Iron Age Vanga Kingdom.[32] The Indo-Aryan suffix Desh is derived from the Sanskrit word deśha, which means "land" or "country". Hence, the name Bangladesh means "Land of Bengal" or "Country of Bengal".[25][26][27]

History

Ancient and classical Bengal

Stone age tools found in the Greater Bengal region indicate human habitation for over 20,000 years.[33] Remnants of Copper Age settlements date back 4,000 years.[33]

Ancient Bengal was settled by Austroasiatics, Tibeto-Burmans, Dravidians and Indo-Aryans in consecutive waves of migration.[34][35] Major urban settlements formed during the Iron Age in the middle of the first millennium BCE,[36] when the Northern Black Polished Ware culture developed in the Indian subcontinent.[37] In 1879, Sir Alexander Cunningham identified the archaeological ruins of Mahasthangarh as the ancient city of Pundranagara, the capital of the Pundra Kingdom mentioned in the Rigveda.[38][39]

The Wari-Bateshwar ruins are regarded by archaeologists as the capital of an ancient janapada, one of the earliest city states in the subcontinent.[40] An indigenous currency of silver punched marked coins dating between 600 BCE and 400 BCE has been found at the site.[40] Excavations of glass beads suggest the city had trading links with Southeast Asia and the Roman world.[41]

Greek and Roman records of the ancient Gangaridai Kingdom, which according to legend deterred the invasion of Alexander the Great, are linked to the fort city in Wari-Bateshwar.[40] The site is also identified with the prosperous trading center of Souanagoura mentioned in Ptolemy's world map.[41] Roman geographers noted the existence of a large and important seaport in southeastern Bengal, corresponding to the modern-day Chittagong region.[42]

The legendary Vanga Kingdom is mentioned in the Indian epic Mahabharata covering the region of Bangladesh. It was described as a seafaring nation of South Asia. According to Sinhalese chronicles, the Bengali Prince Vijaya led a maritime expedition to Sri Lanka, conquering the island and establishing its first recorded kingdom.[43] The Bengali people also embarked on overseas colonization in Southeast Asia, including in modern-day Malaysia and Indonesia.[44]

Bengal was ruled by the Mauryan Empire in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE. With their bastions in the Bengal and Bihar regions (collectively known as Magadha), the Mauryans built the first geographically extensive Iron Age empire in Ancient India. They promoted Jainism and Buddhism. The empire reached its peak under emperor Ashoka. They were eventually succeeded by the Gupta Empire in the 3rd century. According to historian H. C. Roychowdhury, the Gupta dynasty originated in the Varendra region in Bangladesh, corresponding to the modern-day Rajshahi and Rangpur divisions.[45] The Gupta era saw the invention of chess, the concept of zero, the theory of Earth orbiting the Sun, the study of solar and lunar eclipses and the flourishing of Sanskrit literature and drama.[46][47]

In classical antiquity, Bengal was divided between various kingdoms. The Pala Empire stood out as the largest Bengali state established in ancient history, with an empire covering most of the north Indian subcontinent at its height in the 9th century. The Palas were devout Mahayana Buddhists. They strongly patronized art, architecture and education, giving rise to the Pala School of Painting and Sculptural Art,[48] the Somapura Mahavihara and the universities of Nalanda and Vikramshila. The proto-Bengali language emerged under Pala rule. In the 11th-century, the resurgent Hindu Sena dynasty gained power. The Senas were staunch promoters of Brahmanical Hinduism and laid the foundation of Bengali Hinduism. They patronized their own school of Hindu art taking inspiration from their predecessors.[49] The Senas consolidated the caste system in Bengal.[50]

Bengal was also a junction of the Southwestern Silk Road.[13]

Islamic Bengal

Islam arrived on the shores of Bengal in the late first millennium, brought largely by missionaries, Sufis and merchants from the Middle East. Some experts have suggested that early Muslims, including Sa`d ibn Abi Waqqas (an uncle of the Prophet Muhammad), used Bengal as a transit point to travel to China on the Southern Silk Road.[51] The excavation of Abbasid Caliphate coins in Bangladesh indicate a strong trade network during the House of Wisdom Era in Baghdad, when Arab scientists absorbed pre-Islamic Indian and Greek discoveries.[52] This gave rise to the system of Indo-Arabic numerals. Writing in 1154, Al-Idrisi noted a busy shipping route between Chittagong and Basra.[53]

Subsequent Muslim conquest absorbed the culture and achievements of pre-Islamic Bengali civilization in the new Islamic polity.[54] Muslims adopted indigenous customs and traditions, including dress, food, and way of life. This included the wearing of the sari, bindu, and bangles by Muslim women; and art forms in music, dance, and theater.[54] Muslim rule reinforced the process of conversion through the construction of mosques, madrasas and Sufi Khanqahs.[55]

The Islamic conquest of Bengal began when Bakhtiar Khilji of the Delhi Sultanate conquered northern and western Bengal in 1204.[56] The Delhi Sultanate gradually annexed the whole of Bengal over the next century. By the 14th century, an independent Bengal Sultanate was established.[57] The rulers of the Turkic[58][59][60] Ilyas Shahi dynasty built the largest mosque in South Asia, and cultivated strong diplomatic and commercial ties with Ming China.[61][62]

Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah was the first Bengali convert on the throne.[57] The Bengal Sultanate was noted for its cultural pluralism. Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists jointly formed its civil-military services. The Hussain Shahi sultans promoted the development of Bengali literature.[63] It brought Arakan under its suzerainty for 100 years.[64]

The sultanate was visited by numerous world explorers, including Niccolò de' Conti of Venice, Ibn Battuta of Morocco and Admiral Zheng He of China. However, by the 16th century, the Bengal Sultanate began to disintegrate. The Sur Empire overran Bengal in 1532 and built the Grand Trunk Road. Hindu Rajas and the Baro-Bhuyan zamindars gained control of large parts of the region, especially in the fertile Bhati zone. Isa Khan was the Rajput leader of the Baro-Bhuyans based in Sonargaon.[65]

In the late 16th-century, the Mughal Empire led by Akbar the Great began conquering the Bengal delta after the Battle of Tukaroi,[67] where he defeated the Bengal Sultanate's last rulers, the Karrani dynasty. Dhaka was established as the Mughal provincial capital in 1608. The Mughals faced stiff resistance from the Baro-Bhuyans, Afghan warlords and zamindars, but were ultimately successful in conquering the whole of Bengal by 1666, when the Portuguese and Arakanese were expelled from Chittagong. Mughal rule ushered economic prosperity, agrarian reform and flourishing external trade, particularly in muslin and silk textiles. Mughal Viceroys promoted agricultural expansion and turned Bengal into the rice basket of the Indian subcontinent. The Sufis gained increasing prominence. The Baul movement, inspired by Sufism, also emerged under Mughal rule. The Bengali ethnic identity further crystallized during this period, and the region's inhabitants were given sufficient autonomy to cultivate their own customs and literature. The entire region was brought under a stable-long lasting administration.[61]

By the 18th century, the Bengal Subah included the dominions of Bengal proper, Bihar and Orissa. It was the wealthiest part of the subcontinent.[68] It generated 50% of Mughal GDP.[69] Its towns and cities were filled with Eurasian traders. Dhaka became an important center of Mughal administration. The Nawabs of Bengal established an independent principality in 1717, with their headquarters in Murshidabad. The Nawabs granted increasing concessions to European trading powers. Matters reached a climax in 1757, when Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah captured the British base at Fort William, in an effort to stem the rising influence of the East India Company. Siraj-ud-Daulah was betrayed by his general Mir Jafar, who helped Robert Clive defeat the last independent Nawab at the Battle of Plassey on 23 June 1757.[70][71]

British Bengal

The defeat of the last independent Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey ushered the rule of the British East India Company in 1757. The British displaced the ruling Muslim class of Bengal.[72] The Bengal Presidency was established in 1765, with Calcutta as its capital. The Permanent Settlement created an oppressive feudal system. A number of deadly famines struck the region.

The Mutiny of 1857 was initiated in the Presidency of Bengal, with major revolts by the Bengal Army in Dacca, Calcutta and Chittagong.[73][74] Eastern Bengal witnessed numerous native rebellions, including the Faraizi Movement by Haji Shariatullah, the activities of Titumir, the Chittagong armoury raid and revolutionary formations such as the Anushilan Samiti. The Bengal Renaissance flowered as a result of educational and cultural institutions being established across the region, especially in East Bengal and the imperial colonial capital Calcutta. The Presidency of Bengal became the cradle of modern South Asian political and artistic expression. It included the notable contributions of Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Mir Mosharraf Hossain, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Jagadish Chandra Bose, Khan Bahadur Ahsanullah, Rabindranath Tagore, Michael Madhusudan Dutt, Kazi Nazrul Islam and Begum Rokeya. Gopal Krishna Gokhle, the mentor of Mahatma Gandhi, remarked that "what Bengal thinks today, India thinks tomorrow".[75]

During British rule, East Bengal developed a plantation economy centred on the jute trade and tea production. Its share in world jute supply peaked in the early 20th century, at over 80%.[76] The Eastern Bengal Railway and the Assam Bengal Railway served as important trade routes, connecting the Port of Chittagong with a large hinterland.

As a result of growing demands for educational development in East Bengal, the British partitioned Bengal in 1905 and created the administrative division of Eastern Bengal and Assam. Based in Dacca, with Shillong as the summer capital and Chittagong as the chief port, the new province covered much of the northeastern subcontinent. The All India Muslim League was formed in Dacca in 1906 and emerged as the standard bearer of Muslims in British India. The partition of Bengal outraged nationalist Hindus and anti-British Muslims, leading to the Swadeshi movement by the Indian National Congress. The partition was annulled in 1911 after a long civil disobedience campaign by the Congress. The Indian Independence Movement enjoyed strong momentum in the Bengal region, including the constitutional struggle for the rights of Muslim minorities.

The Freedom of Intellect Movement thrived in the University of Dacca. By the 1930s, the Krishak Praja Party led by A. K. Fazlul Huq and the Swaraj Party led by C. R. Das came to represent the new Bengali middle class. Huq became the Prime Minister of Bengal in 1937. With the breakdown of Hindu-Muslim unity in the British Raj, Huq allied with the Muslim League to present the Lahore Resolution in 1940, which envisioned independent states in the eastern and northwestern subcontinent.

During the Second World War, the Japanese Air Force conducted air raids in Chittagong in 1942, displacing several thousand people.[77][78] The war-induced Bengal famine of 1943 claimed the lives of over a million people. Allied forces were stationed in bases across East Bengal in support of the Burma Campaign. Axis-allied Subhash Chandra Bose also had a significant following in East Bengal.

The Muslim League formed a parliamentary government in Bengal in 1943, with Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin and later H. S. Suhrawardy as its premiers. At the Indian provincial elections, 1946, the decisive victory of the Bengal Muslim League set the course for the Partition of British India and the creation of the Dominion of Pakistan on 14 August 1947. Assam was partitioned in order to allow Bengali-speaking Sylhet to join East Bengal. There was also an unsuccessful attempt to form a United Bengal. The Radcliffe Line divided Bengal on religious grounds, ceding Hindu-majority districts to the Indian dominion, and making Muslim-majority districts the eastern wing of Pakistan.

Eastern wing of Pakistan

.svg.png)

East Bengal was the most populous province in the new Pakistani federation led by Governor General Muhammad Ali Jinnah in 1947, with Dacca as the provincial capital.[79] While the state of Pakistan was created as a homeland for Muslims of the former British Raj, East Bengal was also Pakistan's most cosmopolitan province, being home to peoples of different faiths, cultures and ethnic groups. In 1950, land reform was accomplished in East Bengal with the abolishment of the permanent settlement and the feudal zamindari system.[80]

The successful Bengali Language Movement in 1952 was the first sign of friction with West Pakistan.[81] The One Unit scheme renamed the province as East Pakistan in 1955. The Awami League emerged as the political voice of the Bengali-speaking population,[82] with its leader H. S. Suhrawardy becoming Prime Minister of Pakistan in 1956. He was ousted after only a year in office due to tensions with West Pakistan's establishment and bureaucracy.[83]

The 1956 Constitution ended dominion status with Queen Elizabeth II as the last monarch of the country. Dissatisfaction with the central government increased over economic and cultural issues. The provincial government of A. K. Fazlul Huq was dismissed on charges of inciting secession.[84] In 1957, the radical left-wing populist leader Maulana Bhashani warned that the eastern wing would bid farewell to Pakistan.[85]

The first Pakistani military coup ushered the dictatorship of Ayub Khan. In 1962, Dacca was designated as the legislative capital of Pakistan in an appeasement of growing Bengali political nationalism.[86] Khan's government also constructed the Kaptai Dam which controversially displaced the Chakma population from their indigenous homeland in the Chittagong Hill Tracts.[87] During the 1965 presidential election, Fatima Jinnah failed to defeat Field Marshal Ayub Khan despite strong support in East Pakistan.[88]

According to senior international bureaucrats in the World Bank, Pakistan applied extensive economic discrimination against the eastern wing, including higher government spending on West Pakistan, financial transfers from East to West and the use of the East's foreign exchange surpluses to finance the West's imports.[89] This was despite the fact that East Pakistan generated 70%[90] of Pakistan's export earnings with jute and tea.[89] East Pakistani intellectuals crafted the Six Points which called for greater regional autonomy, free trade and economic independence. The Six Points were championed by Awami League President Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1966, leading to his arrest by the government of President Field Marshal Ayub Khan on charges of treason. Rahman was released during the 1969 popular uprising which ousted President Khan from power.

Ethnic and linguistic discrimination was abound in Pakistan's civil and military services, in which Bengalis were hugely under-represented. In Pakistan's central government, only 15% of offices were occupied by East Pakistanis.[91] They formed only 10% of the military.[92] Cultural discrimination also prevailed, causing the eastern wing to forge a distinct political identity.[93] Pakistan imposed bans on Bengali literature and music in state media, including the works of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore.[94] In 1970, a massive cyclone devastated the coast of East Pakistan killing up to half a million people.[95] The central government was criticized for its poor response.[96] After the elections of December 1970, calls for the independence of Bangladesh became stronger.[97]

Genocide and war of independence

The anger of the Bengali population was compounded when Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, whose Awami League had won a majority in Parliament in the 1970 elections, was blocked from taking office.[98] A massive civil disobedience movement erupted across East Pakistan, with open calls for independence.[99] Sheikh Mujibur Rahman addressed a huge pro-independence rally in Dacca on 7 March 1971. The Bangladeshi flag was hoisted for the first time on 23 March 1971, Pakistan's Republic Day.[100]

On 26 March 1971, the Pakistani military junta[101] led by Yahya Khan launched Operation Searchlight, a sustained military assault on East Pakistan,[102][103] and detained the Prime Minister-elect[104][105] under military custody.[106] The Pakistan Army, with the help of supporting militias, massacred Bengali students, intellectuals, politicians, civil servants and military defectors during the 1971 Bangladesh genocide.[107] Several million refugees fled to neighboring India. Estimates for those killed throughout the war range between 300,000 and 3 million.[108]

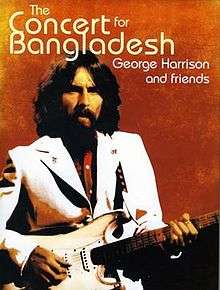

Global public opinion turned against Pakistan as news of atrocities spread,[109] with the Bangladesh Movement gaining support from prominent political and cultural figures in the West, including Ted Kennedy, George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Victoria Ocampo and Andre Malraux.[110][111][112][113] The Concert for Bangla Desh was held at Madison Square Garden in New York City to raise funds for Bangladeshi refugees. It was the first major benefit concert in history and was organized by Beatles star George Harrison and Indian Bengali sitarist Ravi Shankar.[114]

During the liberation war, Bengali nationalists announced a declaration of independence and formed the Mukti Bahini (the Bangladeshi National Liberation Army). The Provisional Government of Bangladesh operated in exile from Calcutta, India. Led by General M. A. G. Osmani and eleven Sector Commanders, the Mukti Bahini held the Bengali countryside during the war, and waged wide-scale guerrilla operations against Pakistani forces. Neighboring India and its leader Indira Gandhi, a longstanding nemesis of Pakistan, provided crucial support to the Bangladesh Forces and intervened in support of the provisional government on 3 December 1971. The Soviet Union and the United States dispatched naval forces to the Bay of Bengal amid a Cold War standoff during the Indo-Pakistani War. Lasting for nine months, the entire war ended with the surrender of Pakistan's military to the Bangladesh-India Allied Forces on 16 December 1971.[115][116] Under international pressure, Pakistan released Mujib from imprisonment on 8 January 1972, after which he was flown by the Royal Air Force to a million strong homecoming in Dhaka.[117][118] Indian troops were withdrawn by 12 March 1972, three months after the war ended.[119]

The cause of Bangladeshi self-determination was widely recognized around the world.[109] By the time of its admission for UN membership in August 1972, the new state was recognized by 86 countries.[109] Pakistan recognized Bangladesh in 1974 after pressure from most of the Muslim world.[120]

Bangladeshi Republic

After independence, Bangladesh became a secular democracy and a republic within the Commonwealth. The world's 7th most populous nation at the time was ravaged by wartime devastation and widespread poverty, receiving massive international aid as a result. It joined the Non-Aligned Movement and the OIC in 1973, followed by the United Nations in 1974. The Mujib administration signed a 25-year friendship treaty with India and was courted by Western and Eastern bloc powers. Bangladesh expressed strong solidarity with Arab countries during the Arab-Israeli War in 1973, sending medical teams to Egypt and Syria.[121][122] Mujib's government faced growing political agitation from left-wing groups, especially the National Socialist Party. Chakma politician M. N. Larma protested the lack of recognition for indigenous Chittagong Hill Tracts minorities in the new constitution.[123] Mujib briefly declared a state of emergency to maintain law and order.

India, Pakistan and Bangladesh signed tripartite agreement in 1973 calling for peace and stability in the subcontinent.[124] A nationwide famine occurred in 1974.[125] In early 1975, Mujib initiated one party socialist rule. On 15 August 1975, Mujib and most of his family members were assassinated by mid-level army officers during a military coup.[126] Vice President Khandaker Mushtaq Ahmed was sworn in as President, with most of Mujib's cabinet intact. Bangladesh was placed under martial law.[127]

Mushtaq interned four prominent associates of Mujib, including Bangladesh's first prime minister Tajuddin Ahmad. Two Army uprisings on 3 and 7 November 1975 led to a reorganised structure of power. Between the two coups, the four interned Awami League leaders were assassinated by army men in Dhaka Central Jail. Mushtaq was replaced by Justice Abu Sayem as President, while the three chiefs of the armed services become martial law administrators. A technocrat cabinet was formed with Moudud Ahmed as Deputy Prime Minister. Bangladesh was one of the first countries to recognize the provisional revolutionary government of South Vietnam after the withdrawal of U.S. forces.[127]

Lieutenant General Ziaur Rahman took over the presidency in 1977 when Justice Sayem resigned. In 1979, President Zia reinstated multi-party politics and restored civilian rule. He promoted free markets and founded the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). Zia reoriented Bangladesh's foreign policy, moving away from the Awami League's strong ties with India and Soviet Union, and pursued closer relations with the West.[128] He opposed the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Domestically, Zia faced as many as 21 coup attempts.[129]

An insurgency began in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, due to demands by the region's indigenous people for autonomy. The Bangladesh Army was accused of persecuting the area's diverse ethnic minorities. Zia also advocated the idea of a South Asian regional community, inspired by the formation of ASEAN.[129] A military crackdown on Rohingyas in neighboring Burma led to an exodus of several hundred thousand refugees into southeastern Bangladesh.[124] Zia's rule ended when he was assassinated by elements of the military in 1981.[126] He was succeeded by Abdus Sattar, who served in office for less than a year.

Bangladesh's next major ruler was Lieutenant General Hussain Muhammad Ershad. As President, Ershad pursued administrative reforms, including a devolution scheme which divided the country into 64 districts and 5 divisions. Ershad hosted the founding summit of SAARC in Dhaka in 1985, which brought together 7 South Asian countries, including India, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Bhutan and Bangladesh, into a landmark regional union.[130] He also expanded the country's road network and started important projects like the Jamuna Bridge. In 1986, Ershad restored civilian rule and founded the Jatiya Party. Elections were held in 1986 and 1988. Ershad sent Bangladeshi troops to join the US-led coalition in the Persian Gulf War after a request from King Fahd.[131] Ershad faced a revolt by opposition parties and the public in 1990, which coupled with pressure from Western donors for democratic reforms, forced him to resign on 6 December that year. He handed over power to Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed. Ershad was later indicted and convicted on corruption charges.[124] In 1991, Bangladesh reverted to parliamentary democracy. Former first lady Khaleda Zia led the Bangladesh Nationalist Party to victory at the general election in 1991 and became the first female Prime Minister in Bangladeshi history. Zia's finance minister Saifur Rahman launched a series of economic reforms aimed at liberalizing the Bangladeshi economy, mirroring similar initiatives by Manmohan Singh in India in 1991. Prime Minister Zia was forced to implement the caretaker government provision in the constitution in 1996 by the opposition.[132]

At the next election in 1996, the Awami League, headed by Sheikh Hasina, one of Mujib's surviving daughters, returned to power after 21 years. Hasina ended the Chittagong Hill Tracts insurgency after a peace accord with PCJSS rebels. She also secured a treaty with India on sharing the water of the Ganges. Hasina held a trilateral economic summit between India, Pakistan and Bangladesh in 1999 and helped establish the D8 grouping with Turkey.[132] The economy took a downturn with a depletion of foreign exchange reserves.[133] Hasina also refused to export Bangladesh's natural gas, despite major investment offers from international oil companies. The Awami League lost again to the Bangladesh Nationalist Party in the 2001 election. In her second term as Prime Minister, Khaleda Zia signed a Defence Cooperation Agreement with China.[134]

The economy picked up steam from 2003, with a GDP growth rate of 6% in spite of the 2005 floods. Zia faced criticism for her alliance with the Jamaat-e-Islami, which was accused of war crimes in 1971, and accusations against her son Tarique Rahman of corruption. The Awami League waged a series of strikes against the government after an assassination attempt on former premier Sheikh Hasina. Widespread political unrest followed the end of the BNP's tenure in late October 2006. A caretaker government led by the pro-BNP President Iajuddin Ahmed worked to bring the parties to election within the required ninety days, but was accused by opposition parties of being biased. At the last minute, the Awami League announced an election boycott.

On 11 January 2007, the Bangladesh Armed Forces intervened to support both a state of emergency and a continuing but neutral caretaker government under a newly appointed Chief Advisor Fakhruddin Ahmed, the former governor of the Bangladesh Bank. Ahmed strengthened the Anti Corruption Commission and launched an anti-graft drive, detaining more than 160 people, including politicians, civil servants, businessmen and two sons of Khaleda Zia. The Awami League won a landslide majority in the 2008 general election.[135][136] The BNP boycotted the general election in 2014 due to Sheikh Hasina's cancellation of the caretaker government system.

Bangladesh has significantly reduced poverty since it gained independence, with the poverty rate coming down from 57% in 1990[137] to 25.6% in 2014.[22] Per-capita incomes have more than doubled from 1975 levels. Bangladesh has also achieved successes in human development, including greater life expectancy than India.[138] The country continues to face challenges of unstable politics, climate change, religious extremism and inequality.

Geography

The geography of Bangladesh is divided between three regions. Most of the country is dominated by the fertile Ganges-Brahmaputra delta. The northwest and central parts of the country are formed by the Madhupur and the Barind plateaus. The northeast and southeast are home to evergreen hill ranges. The Ganges delta is formed by the confluence of the Ganges (local name Padma or Pôdda), Brahmaputra (Jamuna or Jomuna), and Meghna rivers and their respective tributaries. The Ganges unites with the Jamuna (main channel of the Brahmaputra) and later joins the Meghna, finally flowing into the Bay of Bengal. The alluvial soil deposited by the rivers when they overflow their banks has created some of the most fertile plains in the world. Bangladesh has 57 trans-boundary rivers, making water issues politically complicated to resolve – in most cases as the lower riparian state to India.[139]

Bangladesh is predominately rich fertile flat land. Most parts of Bangladesh are less than 12 m (39.4 ft) above sea level, and it is estimated that about 10% of the land would be flooded if the sea level were to rise by 1 m (3.28 ft).[140] 17% of the country is covered by forests and 12% is covered by hill systems. The country's haor wetlands are of significant importance to global environmental science.

In southeastern Bangladesh, experiments have been done since the 1960s to 'build with nature'. Construction of cross dams has induced a natural accretion of silt, creating new land. With Dutch funding, the Bangladeshi government began promoting the development of this new land in the late 1970s. The effort has become a multi-agency endeavor, building roads, culverts, embankments, cyclone shelters, toilets and ponds, as well as distributing land to settlers. By fall 2010, the program will have allotted some 27,000 acres (10,927 ha) to 21,000 families.[141] With an elevation of 1,064 m (3,491 ft), the highest peak of Bangladesh is Keokradong, near the border with Myanmar.

- Landscapes of Bangladesh

-

The fertile Bangladesh Plain seen against the backdrop of the Himalayas

-

.jpg)

A bird among water lilies in a haor wetland

-

.jpg)

Keokradong, one of the highest peaks in Bangladesh

-

Boats on the Cox's Bazar Beach, the longest natural beach in the world

-

Lawachara National Park, a subtropical rainforest in Sylhet Division

-

Sal forests in Gazipur District

Climate

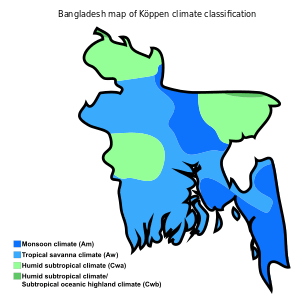

Straddling the Tropic of Cancer, Bangladesh's climate is tropical with a mild winter from October to March, and a hot, humid summer from March to June. The country has never recorded an air temperature below 0 °C, with a record low of 1.1 °C in the north west city of Dinajpur on 3 February 1905.[142] A warm and humid monsoon season lasts from June to October and supplies most of the country's rainfall. Natural calamities, such as floods, tropical cyclones, tornadoes, and tidal bores occur almost every year,[143] combined with the effects of deforestation, soil degradation and erosion. The cyclones of 1970 and 1991 were particularly devastating. A cyclone that struck Bangladesh in 1991 killed some 140,000 people.[144] In September 1998, Bangladesh saw the most severe flooding in modern world history. As the Brahmaputra, the Ganges and Meghna spilt over and swallowed 300,000 houses, 9,700 km (6,000 mi) of road and 2,700 km (1,700 mi) of embankment, 1,000 people were killed and 30 million more were made homeless, with 135,000 cattle killed, 50 km2 (19 sq mi) of land destroyed and 11,000 km (6,800 mi) of roads damaged or destroyed. Two-thirds of the country was underwater. There were several reasons for the severity of the flooding. Firstly, there were unusually high monsoon rains. Secondly, the Himalayas shed off an equally unusually high amount of melt water that year. Thirdly, trees that usually would have intercepted rain water had been cut down for firewood or to make space for animals.[145]

Bangladesh is now widely recognised to be one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change. Natural hazards that come from increased rainfall, rising sea levels, and tropical cyclones are expected to increase as climate changes, each seriously affecting agriculture, water and food security, human health and shelter.[146] It is believed that in the coming decades the rising sea level alone will create more than 20 million[147] climate refugees.[148] Bangladeshi water is contaminated with arsenic frequently because of the high arsenic contents in the soil. Up to 77 million people are exposed to toxic arsenic from drinking water.[149][150]

Bangladesh is prone to floods, tornados and cyclones.[151][152] Also, there is evidence that earthquakes pose a threat to the country. Evidence shows that tectonics have caused rivers to shift course suddenly and dramatically. It has been shown that rainy-season flooding in Bangladesh, on the world's largest river delta, can push the underlying crust down by as much as 6 centimetres, and possibly perturb faults.[153]

Biodiversity

Bangladesh ratified the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 3 May 1994.[154] As of 2014, the country is set to revise its National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan.[154]

Bangladesh is located in the Indomalaya ecozone. Its ecology includes a long sea coastline, numerous rivers and tributaries, lakes, wetlands, evergreen forests, semi evergreen forests, hill forests, moist deciduous forests, freshwater swamp forests and flat land with tall grass. The Bangladesh Plain is famous for its fertile alluvial soil which supports extensive cultivation. The country is dominated by lush vegetation, with villages often buried in groves of mango, jackfruit, bamboo, betel nut, coconut and date palm.[155] There are 6000 species of plant life, including 5000 flowering plants.[156] Water bodies and wetland systems provide a habitat for many aquatic plants. Water lilies and lotuses grow vividly during the monsoon. The country has 50 wildlife sanctuaries.

Bangladesh is home to much of the Sundarbans, the world's largest mangrove forest. It covers an area of 6,000 km2 in the southwest littoral region. It is divided into three protected sanctuaries- the South, East and West zones. The forest is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The northeastern Sylhet region is home to haor wetlands, which is a unique ecosystem. It also includes tropical and subtropical coniferous forests, a freshwater swamp forest and mixed deciduous forests. The southeastern Chittagong region covers evergreen and semi evergreen hilly jungles. Central Bangladesh includes the plainland Sal forest running along the districts of Gazipur, Tangail and Mymensingh. St. Martin's Island is the only coral reef in the country.

Bangladesh has an abundance of wildlife in its forests, marshes, woodlands and hills.[155] The vast majority of animals dwell within a habitat of 150,000 km2.[157] The Bengal tiger, clouded leopard, saltwater crocodile, black panther and fishing cat are among the chief predators in the Sundarbans.[158][159] Northern and eastern Bangladesh is home to the Asian elephant, hoolock gibbon, Asian black bear and oriental pied hornbill.[160]

The Chital deer are widely seen in southwestern woodlands. Other animals include the black giant squirrel, capped langur, Bengal fox, sambar deer, jungle cat, king cobra, wild boar, mongooses, pangolins, pythons and water monitors. Bangladesh has one of the largest population of Irrawaddy dolphins and Ganges dolphins. A 2009 census found 6,000 Irrawaddy dolphins inhabiting the littoral rivers of Bangladesh.[161] The country has numerous species of amphibians (53), reptiles (139), marine reptiles (19) and marine mammals (5). It has 628 species of birds.[162]

Several animals became extinct in Bangladesh during the last century, including the one horned and two horned rhinoceros and common peafowl. The human population is concentrated in urban areas, hence limiting deforestation to a certain extent. Rapid urban growth has threatened natural habitats. Though many areas are protected under law, a large portion of Bangladeshi wildlife is threatened by this growth. The Bangladesh Environment Conservation Act was enacted in 1995. The government has designated several regions as Ecologically Critical Areas, including wetlands, forests and rivers. The Sundarbans Tiger Project and the Bangladesh Bear Project are among the key initiatives to strengthen conservation.[160]

Politics

Government

The politics of Bangladesh takes place in the framework of a multiparty parliamentary representative democracy, modeled on the Westminster system of unicameral parliamentary government. Traditionally, Bangladesh has been a two party system since democracy was restored in 1990. However, concerns over the fairness of elections and annulment of the caretaker government system led to a boycott of the national election in 2014 by major opposition parties. Critics have accused the government of trying to turn Bangladesh into a dominant party state under the ruling Awami League.[163]

The Bangladeshi state has a unitary structure, with the central government in Dhaka.

- Executive: The Prime Minister is the head of government and is appointed by the President with the confidence of the majority in parliament. The Prime Minister heads the Cabinet of Bangladesh which holds Executive power. The President is the head of state with key ceremonial duties. The President is elected by the parliament for a five-year term. Sheikh Hasina has been the Prime Minister of Bangladesh since 2009. Abdul Hamid is the current President of Bangladesh.

- Legislative: There are 350 MPs in the Jatiyo Sangshad.[164] It is headed by the Speaker of Parliament, who is second in line to the presidency. The Prime Minister is traditionally the Leader of the House and the single largest party. The Leader of the Opposition heads the main opposition in the house. During elections, 300 lawmakers are elected on a first-past-the-post basis.[165] The Speaker allocates an additional 50 reserved seats for women candidates. The Awami League currently holds control of the house with 273 seats. The Jatiya Party is the chief opposition with 42 seats. The current Speaker of parliament is Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury.

- Judicial: The legal system of Bangladesh is primarily in accordance with English Common Law.[166] The higher judiciary consists of the Supreme Court, which includes an Appellate Division and the Bangladesh High Court. The current Chief Justice is Surendra Kumar Sinha. The constitution has undergone fifteen amendments since 1972.

Foreign affairs

Bangladesh's foreign policy follows a principle of friendship to all and malice to none, which was first articulated by Bengali statesman H. S. Suhrawardy in 1957.[167][168] Suhrawardy also led East and West Pakistan to join the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, CENTO and the Regional Cooperation for Development. After independence, Bangladesh joined the Commonwealth of Nations and the United Nations. Today, countries considered as Bangladesh's most important partners include India,[169] China,[170] Japan,[171] Saudi Arabia,[172] Russia,[173] the United States[174] and the United Kingdom.[175]

During the Cold War, Bangladesh cultivated good relations with both the United States and the Soviet Union, but it remained nonaligned with either superpower.[176] Bangladesh asserted itself in regards to many international issues, including those affecting decolonized and developing countries.[176] Bangladesh traditionally places a heavy reliance on multilateral diplomacy, especially in the United Nations. Since independence, it has twice been elected to the UN Security Council. Bangladeshi diplomat Humayun Rashid Choudhury served as President of the United Nations General Assembly.[177]

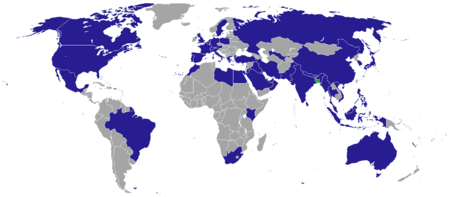

During the Gulf War in 1991, Bangladesh contributed 2,300 troops to the US-led multinational coalition for the liberation of Kuwait. It has since become the world's largest contributor of UN peacekeeping forces, providing 113,000 personnel to 54 UN missions in the Middle East, the Balkans, Africa and the Caribbean, as of 2014.[178] Bangladeshi aid agencies work in many developing countries worldwide. An example are the operations of BRAC in Afghanistan, which benefit 12 million people in that country.[179]

Bangladeshi foreign policy also relies on the country's Islamic heritage, being an OIC member and the world's third largest Muslim-majority country, and enjoys fraternal relations with many nations in the Muslim world. It is a founding member of the Developing 8, along with Turkey, Malaysia, Egypt, Iran, Nigeria, Pakistan and Indonesia.[176]

Strategically important in South Asia and the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh is classified as a middle power. It has diverse political, economic and military partnerships in the region.[176] It has played a leading role in organizing regional engagement and development cooperation. The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) was founded in Dhaka in 1985. Three Bangladeshis have since served as its Secretary General. The Bangladeshi capital hosts the headquarters of the Bay of Bengal Initiative (BIMSTEC). The country is part of the Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar Forum for Regional Cooperation. It has prioritized relations with ASEAN members in Southeast Asia. It is a member of the Indian Ocean Rim Association.

Bangladesh's most important bilateral relations are with the two regional powers India and China. The relationship with India is bound by shared ideals of democracy, cultural heritage and the 1971 Liberation War, in which Indian military and diplomatic support was crucial in defeating Pakistani forces on Bangladeshi territory. In the early years of Bangladesh's independence, Dhaka and Delhi enjoyed a strong alliance. However, when military coups began in Bangladesh during the late 1970s, there was increasing distance between the two neighbors. Differences emerged over sharing the water of the Ganges. Bangladesh developed very warm relations with the People's Republic of China in the 1980s. Defense cooperation rapidly increased as the Bangladeshi military became one of the largest buyers of Chinese defense equipment, given their relative cost-effective attractiveness for the Bangladeshi defence budget.[180] China has supplied Bangladesh with missiles and frigates. China is also one of Bangladesh's largest trade partners. In more recent years, India has sought to revive relations with Bangladesh through a strategic partnership focused on counter-terrorism, aid for infrastructure development and promoting regional economic integration. Bangladesh and India are the largest trading partners among SAARC nations. The Indian and Bangladeshi armed forces maintain robust strategic engagement. Relations with Pakistan have been affected by issues related to the 1971 genocide and terrorism. Bangladesh enjoys strong ties with regional neighbors Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka and the Maldives.

Bangladesh's relations with neighboring Myanmar are relatively warm. Myanmar was one of the first countries to recognize Bangladesh's independence. Relations were in a brief deadlock due to a naval standoff in 2008 over disputed maritime territory.[181] In 2012, the two countries resolved their maritime boundary disputes at the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea.[182] The relationship with Myanmar is complicated by the persecution of the Rohingya people in Rakhine State. As of 2016, Bangladesh hosts between 300,000 and 500,000 Rohingya refugees who have fled Myanmarese military crackdowns since 1978.[183] In 2012, Bangladesh denied entry to further refugees after another spate of sectarian riots broke out in Rakhine State.[184] Both countries view each other as gateways to South and Southeast Asia. Their armed forces maintain regular dialogue and both depend on Chinese military supplies. Thailand is an important ally and economic partner of Bangladesh, with the two countries sharing strategic interests in the Bay of Bengal region.

The United States enjoys a warm and strategic partnership with Bangladesh. 76% of Bangladeshis viewed the United States favorably in 2014.[185] The United States is Bangladesh's largest foreign investor and trade partner. Bangladesh is the third largest recipient of American development assistance in Asia after Afghanistan and Pakistan.[186] Relations with the United Kingdom are long-standing. Bangladesh is one of the largest recipients of U.K. development aid. Japan and Bangladesh have strong relations with common strategic and political goals.[167] Japan has been Bangladesh's largest development partner since independence, providing over US$11 billion in aid.[187] Relations with the Russian Federation have focused on trade, nuclear energy and defense supplies. There are also growing trade links with Latin American nations, particularly Brazil and Mexico.

Bangladesh has a strong record of nuclear nonproliferation as a party to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT).[188]

Military

As of 2012, the current strength of the army is around 300,000 including reservists,[189] the air force 22,000, and navy 24,000.[190] In addition to traditional defence roles, the military has been called on to provide support to civil authorities for disaster relief and internal security during periods of political unrest. Bangladesh has consistently been the world's largest contributor to UN peacekeeping forces for many years. In February 2015, Bangladesh had major deployments in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Darfur, Côte d'Ivoire, Haiti, South Sudan, Lebanon, Cyprus and the Golan Heights.[191]

Human rights and corruption

.jpg)

Bangladesh is ranked by Freedom House as "Partly Free" in its Freedom in the World report.[192] Press freedom in Bangladesh is ranked as "Not Free".[193] The Economist Intelligence Unit classifies the country as a hybrid regime, which is the third best rank out of four in its Democracy Index.[194] Bangladesh ranked as the 3rd most peaceful country in South Asia in the Global Peace Index in 2015.[195] In recent years, the once vibrant civil society and media in Bangladesh have come under attack from both the ruling Awami League government and far-right Islamic extremists.[196]

According to Mizanur Rahman, the chairman of the National Human Rights Commission, 70% of the allegations of human rights violations they receive are against the law-enforcement agencies.[197] Targets have included Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus and the Grameen Bank, secularist bloggers, independent and pro-opposition newspapers and television networks. The United Nations has said that it was deeply concerned by the government's "measures that restrict freedom of expression and democratic space".[196]

Bangladeshi security forces, particularly the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), have faced strong international condemnation for human rights abuses, including enforced disappearances, torture and extrajudicial killings. Over 1,000 people have been killed in extrajudicial killings by RAB since its inception under the last BNP government.[198] The agency has been singled out by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International as a "death squad".[199][200] They have called for the force to be disbanded.[199][200] The British and American governments have been widely criticized for funding and engaging the force in counter-terrorism operations.[201]

In the Chittagong Hill Tracts, the government is yet to fully implement the Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord.[202] The Hill Tracts region remains heavily militarized despite the signing of the peace treaty with indigenous people led by the United People's Party of the Chittagong Hill Tracts.[203]

Secularism in Bangladesh is legally enshrined in the constitution. Religious parties are banned from contesting elections, but the government is accused of courting religious extremist groups for votes. Ambiguities over Islam being the state religion have been criticized by the United Nations.[204] Despite relative inter-religious and communal harmony, minorities in Bangladesh have faced persecution on occasions. The Hindu and Buddhist communities have faced religious violence from Islamic groups, notably the Jamaat-e-Islami and its student wing Shibir. The highest vote share achieved by Islamic far right candidates during Bangladeshi elections was 12% in 2001; the lowest was 4% in 2008.[205]

According to Transparency International, Bangladesh ranked 14th in the list of countries with the most perceived corruption in 2014.[206] The country's Anti Corruption Commission was highly active under a state of emergency in 2007 and 2008, when it indicted many leading politicians, bureaucrats and businessmen for graft. After assuming power in 2009, the Awami League government greatly reduced the commission's independent powers for investigation and prosecution.[207]

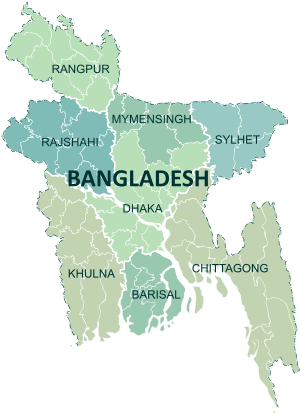

Administrative divisions

Bangladesh is divided into eight administrative divisions,[208][209][210] each named after their respective divisional headquarters: Barisal, Chittagong, Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, Sylhet and Rangpur.

Divisions are subdivided into districts (zila). There are 64 districts in Bangladesh, each further subdivided into upazila (subdistricts) or thana. The area within each police station, except for those in metropolitan areas, is divided into several unions, with each union consisting of multiple villages. In the metropolitan areas, police stations are divided into wards, which are further divided into mahallas.

There are no elected officials at the divisional or district levels, and the administration is composed only of government officials. Direct elections are held for each union (or ward), electing a chairperson and a number of members. In 1997, a parliamentary act was passed to reserve three seats (out of 12) in every union for female candidates.[211]

| Administrative Divisions of Bangladesh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division | Capital | Established | Area (km2)[212] | Population[212] | Density[212] | ||

| Barisal | Barisal | ||||||

| Chittagong | Chittagong | |

|||||

| Dhaka | Dhaka | |

|

|

| ||

| Khulna | Khulna | |

|

|

| ||

| Mymensingh | Mymensingh | |

|

|

| ||

| Rajshahi | Rajshahi | |

|

|

| ||

| Rangpur | Rangpur | |

|

|

| ||

| Sylhet | Sylhet | 1 August 1995 | |

|

| ||

Economy

.jpg)

Bangladesh is a developing country, with a market-based mixed economy and is listed as one of the Next Eleven emerging markets. The per capita income of Bangladesh was US$1,190 in 2014, with a GDP of US$209 billion.[213] In South Asia, Bangladesh has the third-largest economy after those of India and Pakistan, and has the second highest foreign exchange reserves after India. The Bangladeshi diaspora contributed US$15.31 billion in remittances in 2015.[214]

In the early five years of independence, Bangladesh adopted socialist policies which proved to be a critical blunder by the Awami League.[215] The subsequent military regime and BNP and Jatiya Party governments restored free markets and promoted the Bangladeshi private sector. In 1991, finance minister Saifur Rahman launched a range of liberal reforms. The Bangladeshi private sector has since rapidly expanded, with numerous conglomerates now driving the economy. Major industries include textiles, pharmaceuticals, shipbuilding, steel, electronics, energy, construction materials, chemicals, ceramics, food processing, and leather goods. Export-oriented industrialization has increased in recent years, with the country's exports amounting to US$30 billion in FY2014-15.[216] The predominant export earnings of Bangladesh come from its garments sector. The country also has a vibrant social enterprise sector, including the Nobel Peace Prize-winning microfinance institution Grameen Bank and the world's largest non-governmental development agency BRAC.

The insufficient power supply is a significant obstacle to growth. According to the World Bank, poor governance, corruption and weak public institutions are major challenges for Bangladesh's development.[217] In April 2010, Standard & Poor's awarded Bangladesh a BB- long term credit rating, which is below India and well above Pakistan and Sri Lanka.[218]

Primary

Bangladesh is notable for its fertile land, including the Ganges delta, the Sylhet Division and the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Agriculture is the single largest producing sector of the economy since it comprises about 18.6% (data released on November 2010) of the country's GDP and employs around 45% of the total labor force.[219] The performance of this sector has an overwhelming impact on major macroeconomic objectives like employment generation, poverty alleviation, human resources development and food security. A plurality of Bangladeshis earn their living from agriculture. The country ranks among the top producers of rice (4th), potatoes (7th), tropical fruits (6th), jute (2nd), and farmed fish (5th).[220][221]

Bangladesh is the 7th largest natural gas producer in Asia, ahead of its neighbor Myanmar. Gas supplies generate 56% of the country's electricity. Major gas fields are located in northeastern (particularly Sylhet) and southern (including Barisal and Chittagong) regions. Petrobangla is the national energy company. The American multinational Chevron produces 50% of Bangladesh's natural gas.[222] According to geologists, the Bay of Bengal holds large untapped gas reserves in Bangladesh' exclusive economic zone.[223] The country also has substantial reserves of coal, with several coal mines operating in northwestern Bangladesh.

Jute exports continue to be significant, however the global jute trade has reduced considerably since it peaked during World War II. Bangladesh has one of the oldest tea industries in the world. It is also major exporter of fish and seafood.

Secondary

The Bangladesh textile industry and Bangladeshi RMG Sector are the largest manufacturing sector, accounting for US$25 billion in exports in 2014.[224] Leather goods manufacturing, particularly in footwear, is the second largest export oriented industrial sector. The pharmaceutical industry in Bangladesh meets 97% of domestic demand and exports to 52 countries.[225][226] The shipbuilding industry in Bangladesh has seen rapid growth with exports to Europe.[227]

The steel industry in Bangladesh is concentrated in the port city of Chittagong. The ceramics industry in Bangladesh is a prominent player in the international ceramics trade. In 2005, Bangladesh was the world's 20th largest cement producer. The country's cement industry depends on limestone imports from North East India. Food processing is a major sector of the local economy, with prominent brands like PRAN that are increasingly gaining an international market. The electronics industry in Bangladesh is witnessing rapid growth, with the Walton Group being its dominant player.[228] Bangladesh also has its own defense industry, including the establishments such as Bangladesh Ordnance Factories and the Khulna Shipyard.

Tertiary

The service sector accounts for 51% of GDP. Bangladesh ranks with Pakistan in having the second largest banking sector in South Asia.[229] The Dhaka Stock Exchange and the Chittagong Stock Exchange are the twin financial markets of the country. The telecoms industry in Bangladesh is one of the fastest growing markets in the world, with 114 million cellphone subscribers in December 2013.[230] The main telecom companies are Grameenphone, Banglalink, Robi, Airtel and BTTB. Tourism in Bangladesh is a developing sector, with the beach resort town of Cox's Bazar being the center of the industry. The Sylhet region, home to Bangladesh's tea country, also receives a large number of visitors. Bangladesh has three UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and five tentative listed sites.

Microfinance was pioneered in Bangladesh by Muhammad Yunus and has been replicated in many countries. There are more than 35 million microcredit borrowers.[231]

Transport

Transport is a major sector in the Bangladesh economy. The aviation industry has seen rapid growth and includes the national flag carrier Biman and other privately owned airlines. The country has a 2,706 km rail network operated by the Bangladesh Railway. It has one of the largest inland waterway networks in the world,[232] with 8,046 km of navigable waterways. The southeastern Port of Chittagong is its busiest seaport, handling over US$60 billion in annual trade.[233] More than 80% of the country's export-import trade passes through Chittagong.

The second busiest seaport is Mongla in southwestern Bangladesh.

Energy

Electricity generation in Bangladesh had an installed capacity of 10,289 MW in January 2014.[234] Commercial energy consumption is mostly natural gas (around 56%), followed by oil, hydropower and coal.

Bangladesh has planned to import hydropower from Bhutan and Nepal.[235]

Nuclear energy in Bangladesh is being developed with Russia in the landmark Ruppur Nuclear Power Plant project.[236]

In renewable energy, Bangladesh has the fifth-largest number of green jobs in the world. Solar panels are increasingly used to power both urban and off grid rural areas.[237]

Water

The share of the population with access to an improved water source was estimated at 98% in 2004,[238] a very high level for a low-income country. This has been achieved to a large extent through the construction of handpumps with the support of external donors. However, in 1993 it was discovered that groundwater, the source of drinking water for 97% of the rural population and a significant share of the urban population, is in many cases naturally contaminated with arsenic.

Another challenge is the low level of cost recovery due to low tariffs and poor economic efficiency, especially in urban areas where revenues from water sales do not even cover operating costs. Concerning sanitation, estimated 56% of the population have had access to adequate sanitation facilities in 2010.[239] A new approach to improve sanitation coverage in rural areas, the community-led total sanitation concept that has been first introduced in Bangladesh, is credited for having contributed significantly to the increase in sanitation coverage since 2000.[240]

Science and technology

SPARRSO, Bangladesh's space agency, was founded in 1983 with assistance from the United States.[241] Bangladesh plans to launch the Bangabandhu-1 communications satellite in 2018.[242] The Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission operates a TRIGA research reactor at its atomic energy facility in Savar.[243] The Bangladesh Council of Scientific and Industrial Research was founded in 1973, and traces to its roots to the East Pakistan Regional Laboratories established in Dhaka (1955), Rajshahi (1965) and Chittagong (1967).

IT Outsourcing

Bangladesh has a large number of trained IT professionals. But as the majority of the businesses have not become large enough and on the other hand due to negligence from the part of business owners to understand the benefits of using software and technology in businesses the local demand for these highly skilled professionals has been low. As a result, the IT industry in Bangladesh has turned its focus on exporting software and it services. Currently it is in 26th position of global IT outsourcing destination.[244] The primary reason behind this is Bangladeshi IT companies are providing high quality services at a much lower cost than its competitors. It is currently estimated that the volume of IT outsourcing is doubling every year in Bangladesh. Several Bangladeshi IT companies has been successful in the global enterprise software market. Bangladeshi Government is envisioning IT sector as the second largest export sector after Garments in the coming years.

Demographics

| Historical populations in millions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1971 | 67.8 | — |

| 1980 | 80.6 | +1.94% |

| 1990 | 105.3 | +2.71% |

| 2000 | 129.6 | +2.10% |

| 2010 | 148.7 | +1.38% |

| 2012 | 161.1 | +4.09% |

| Source: OECD/World Bank[245] | ||

Estimates of the Bangladeshi population vary but most recent data suggest 162 to 168 million people (2015). However, the 2011 census estimated 142.3 million,[246] much less than recent (2007–2010) estimates of Bangladesh's population ranging from 150 to 170 million. Bangladesh is thus the 8th most populous nation in the world. In 1951, the population was only 44 million.[247] It is also the most densely populated large country in the world, and it ranks 11th in population density, when very small countries and city-states are included.[248]

Bangladesh's population growth rate was among the highest in the world in the 1960s and 1970s, when its population grew from 65 to 110 million. With the promotion of birth control in the 1980s, the growth rate began to slow. The fertility rate now stands at 2.55, lower than India (2.58) and Pakistan (3.07) The population is relatively young, with 34% aged 15 or younger and 5% 65 or older. Life expectancy at birth is estimated to be 70 years for both males and females in 2012.[209] Despite the rapid economic growth, 43% of the country still lives below the international poverty line which means living on less than $1.25 per day.[249] Bengalis constitute 98% of the population.[250]

Minorities include indigenous people in the Chittagong Hill Tracts and other parts of northern Bangladesh. The Hill Tracts are home to 11 ethnic tribal groups, notably the Chakma, Marma, Tanchangya, Tripuri, Kuki, Khiang, Khumi, Murang, Mru, Chak, Lushei and Bawm. The Sylhet Division is home to the Bishnupriya Manipuri, Khasi and Jaintia tribes. The Mymensingh District has a substantial Garo population. The northern Bangladesh region is home to aboriginal Santal, Munda and Oraon people. Bangladesh is also home to a significant Ismaili community.[251]

The southeastern region has received an influx of Rohingya refugees from Burma, particularly during Burmese military crackdowns in 1978 and 1991.[252] During renewed sectarian unrest in Rakhine State in 2012, Bangladesh closed its borders amid fears of a third major exodus from Burma.[253] Stranded Pakistanis or Biharis are a contentious dispute between Bangladesh and Pakistan. In 2008, the Bangladesh High Court granted full citizenship to all second generation Stranded Pakistanis born after 1971.[254] The Hill Tracts region suffered unrest and an insurgency from 1975 to 1997 due to a movement by indigenous people for autonomy. A peace accord was signed in 1997; however, the region remains heavily militarized.[255]

Urban centres

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Division | Pop. | Rank | Name | Division | Pop. | ||

Dhaka  Chittagong |

1 | Dhaka | Dhaka | 7,033,076 | 11 | Rangpur | Rangpur | 294,265 |  Khulna  Narayanganj |

| 2 | Chittagong | Chittagong | 2,592,439 | 12 | Mymensingh | Mymensingh | 258,040 | ||

| 3 | Khulna | Khulna | 663,342 | 13 | Gazipur | Dhaka | 213,061 | ||

| 4 | Narayanganj | Dhaka | 543,090 | 14 | Jessore | Khulna | 201,796 | ||

| 5 | Sylhet | Sylhet | 479,837 | 15 | Dinajpur | Rangpur | 186,727 | ||

| 6 | Tongi | Dhaka | 476,350 | 16 | Nawabganj | Rajshahi | 180,731 | ||

| 7 | Rajshahi | Rajshahi | 449,756 | 17 | Brahmanbaria | Chittagong | 172,017 | ||

| 8 | Bogra | Rajshahi | 350,397 | 18 | Cox's Bazar | Chittagong | 167,477 | ||

| 9 | Barisal | Barisal | 328,278 | 19 | Tangail | Dhaka | 167,412 | ||

| 10 | Comilla | Chittagong | 326,386 | 20 | Chandpur | Chittagong | 159,021 | ||

Dhaka is the capital and largest city of Bangladesh. The cities with a city corporation, having mayoral elections, include Dhaka South, Dhaka North, Chittagong, Khulna, Sylhet, Rajshahi, Barisal, Rangpur, Comilla and Gazipur. Other major cities, these and other municipalities electing a chairperson, include Mymensingh, Gopalganj, Jessore, Bogra, Dinajpur, Saidpur, Narayanganj and Rangamati. Both the municipal heads are elected for a span of five years.

Languages

Bangla (Bengali) being the sole official language,[257] English is sometimes used secondarily for official purposes, especially in the judiciary.

More than 98% of Bangladeshis speak Bangla as their native language.[258][259] English is also used as a second language among the middle and upper classes and is also widely used in higher education and the legal system.[260] Historically, laws were written in English and were not translated into Bangla until 1987. Bangladesh's Constitution and all laws are now in both English and Bangla.[261]

Stranded Pakistani Biharis since 1971 living in various camps in Bangladesh speak Urdu.[262] Similarly, Rohingya Refugees from Burma since 1978 living in various camps in Bangladesh speak Rohingya.[263] There are also several indigenous minority languages.

Religion

Islam is the largest religion in Bangladesh, adhered to by about 88% of the population. The country is home to most Bengali Muslims, the second largest ethnic group in the Muslim world. The majority of Bangladeshi Muslims are Sunni, followed by the Shia and Ahmadiya. Roughly 4% are non-denominational Muslims.[265] Bangladesh has the fourth-largest Muslim population in the world and is the third-largest Muslim-majority country after Indonesia and Pakistan.[266]

Hinduism is followed by about 11% of the population, with most being Bengali Hindus and a small segment being ethnic people. Bangladeshi Hindus are the country's second biggest religious group and the third largest Hindu community in the world after those of India and Nepal. Hindus in Bangladesh are almost evenly distributed in all regions, with large concentrations in Gopalganj, Dinajpur, Sylhet, Sunamganj, Mymensingh, Khulna, Jessore, Chittagong and parts of Chittagong Hill Tracts. And despite their dwindling numbers, Hindus are the second-largest religious community after the Muslims in Dhaka.

Buddhism is the third largest religion, at 0.6%. Bangladeshi Buddhists are largely concentrated among ethnic groups in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, particularly the Chakma, Marma and Tanchangya peoples; while coastal Chittagong is home to the large number of Bengali Buddhists.

Christianity is the fourth largest religion at 0.3%.[267]

The remaining 0.1% population follow various folk religions and animistic faiths.

Many people in Bangladesh practice Sufism, which has a long heritage in the region.[268] The largest gathering of Muslims in the country is the Bishwa Ijtema, held annually by the Tablighi Jamaat. The Ijtema is the second largest Muslim congregation in the world after the Hajj.

The Constitution of Bangladesh declares Islam as the state religion, but bans religion-based politics. It proclaims equal recognition of Hindus, Buddhists, Christians and people of all faiths.[269] Earlier in 1972, Bangladesh became the first constitutionally secular country in South Asia.[270] The U. S. State Department describes Bangladesh as a secular pluralistic democracy.[271]

Education

Bangladesh has a low literacy rate, estimated at 66.5% for males and 63.1% for females in 2014.[209] The educational system in Bangladesh is three-tiered and highly subsidized. The government operates many schools in the primary, secondary, and higher secondary levels. It subsidises parts of the funding for many private schools. In the tertiary education sector, the government funds more than 15 state universities through the University Grants Commission.

The education system is divided into five levels: Primary (from grades 1 to 5), Junior Secondary (from grades 6 to 8), Secondary (from grades 9 to 10), Higher Secondary (from grades 11 to 12) and tertiary.[272] The five years of lower secondary education concluded with a Secondary School Certificate (SSC) examination, but since 2009 it concludes with a Primary Education Closing (PEC) examination. Earlier, students who pass this examination proceed to four years secondary or matriculation training, which culminate in a Secondary School Certificate (SSC) Examination.[272]

.jpg)

Primary Education Closing (PEC) passed examinees proceed to three years Junior Secondary, which culminate in a Junior School Certificate (JSC) Examination. Students who pass this examination proceed to two years secondary or matriculation training, which culminate in a Secondary School Certificate (SSC) examination. Students who pass this examination proceed to two years of Higher Secondary or intermediate training, which culminate in a Higher Secondary School Certificate (HSC) examination.[272]

Education is mainly offered in Bengali, but English is commonly taught and used. A large number of Muslim families send their children to attend part-time courses or even to pursue full-time religious education, which is imparted in Bengali and Arabic in madrasahs.[272]

Bangladesh conforms fully to the Education For All (EFA) objectives, the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) and international declarations. Article 17 of the Bangladesh Constitution provides that all children between the ages of six and ten years receive a basic education free of charge.

Universities in Bangladesh are mainly categorized into three types: public (government owned and subsidized), private (private sector owned universities) and international (operated and funded by international organizations). Bangladesh has 34 public, 64 private and two international universities. Bangladesh National University has the largest enrollment among them and University of Dhaka (established 1921) is the oldest. Islamic University of Technology, commonly known as IUT, is a subsidiary organ of the Organisation of the Islamic Cooperation (OIC), representing 57 member countries from Asia, Africa, Europe and South America. Asian University for Women in Chittagong is the preeminent liberal arts university for women in South Asia, representing 14 countries from Asia. The faculty members are from many well-known academic institutions of North America, Europe, Asia, Australia, and the Middle East.[273] BUET, CUET, KUET, RUET are the four public engineering universities in the country. BUTex and DUET are two specialized engineering universities, where BUTex specializes in Textile Engineering and DUET offers higher education to Diploma Engineers. There are some science and technology universities including SUST, MIST, PUST, etc.

Bangladeshi universities are accredited by and affiliated with the University Grants Commission (UGC), created according to the Presidential Order (P.O. No 10 of 1973) of the government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh.[274]

Medical education is provided by 29 government and some other private medical colleges. All medical colleges are affiliated with Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.